We are making our way down the Noatak, now more than 150 river miles from its head waters. Along the way, we passed a grizzly sow lounging with her cub on the river bank, saw dozens of Dahl sheep grazing on rocky knolls, and woke a sleeping musk ox with a startled snort. Harriers and rough-legged hawks float above the tundra and flocks of snow geese pass noisily overhead. On a rare clear night, we heard wolves yapping under a nearly full moon as shadows danced on our frosty tent. The boxes we packed half a year ago contained most of what we remembered and we’re loving the luxuries of a stove and plenty of food. The only intruder on an otherwise pleasant river trip is the weather. It has now been three weeks since we’ve seen a day without significant precipitation – mostly rain, sometimes sleet, snow or hail. On the few occasions when the sun peeks out, it’s often raining at the same time. Where is all this moisture coming from?! It’s tough to stay warm while paddling, even with our many layers – insulated jacket, fleece tights, two hats, three hoods, rain gear, garbage bag poncho for when the jacket gets saturated. The wind seems to blow mostly upriver, adding to the chill. With so much rain, the river is high, its sod banks collapsing into the muddy water, gravel bars fully submerged. The upside of the wet weather is that the current is flushing us swiftly downriver towards the coast. We’ve managed to stay just ahead of the snow so far, but it is creeping ever closer down the mountainside, reminding us that winter in the arctic is not far behind.

Resupply /

200 calorie per day diet has finally ended. Our resupply flight arrived this evening! We've eaten more in the last 20 minutes than we did in the last four days. Hope to be on the river shortly.

Still Waiting /

The 16th day of rain and still no resupply flight. We got flooded out of our first site so moved to higher ground in a downpour. Because we were already stretched thin on the last leg with a two day delay from snow and route change rations are down to one granola bar per day. This awful waiting game is not the reward we had anticipated. But so far we're doing ok, just very hungry and dreaming of food.

Waiting /

Boots, thermos, stove, warm clothes, canoe, more food. These are the treats that we hope will arrive via floatplane today as we wait for our resupply on the Noatak River. After our last post we decided to give Ariel one more try, dreading the alternative and hopeful that the rain had melted some of the snow up high. It soon became apparent that this was not the case and rain turned to sleet and then a full blown blizzard as we reached the 6300 foot summit ridge. With dense, knee deep snow and heavy fog, we didn’t feel we could traverse down the other side safely. A slip could be fatal and we worried about avalanches from the slabs above so were forced to retreat. That evening, as we left the Arrigetch valley, it poured and snow line dropped to 3500 feet. Clearly this wasn’t the sort of weather we could afford to wait out. So we crashed through the bushes, finding occasional game trails but mostly slow laborious travel as we climbed up and down many thousands of feet across drainages. With continued rain and snow, the hillsides gushed water and we inflated our rafts to cross the flooded Awlinyak Creek. Finally cresting out of creek, we reached a beautiful ridge and passed caribou grazing in the high country. For the first time in many days, we ate dinner without rain. By the next morning the drizzle had started again and it rained on and off as we hiked up an unnamed creek to Akabluak Pass. Here we headed west over a steep rocky 5000 foot gap that would lead us to the Noatak drainage.

Bad enough when wet, this big, loose talus felt downright treacherous covered in 4-5 inches of snow. The descent was much worse, taking nearly two hours to slip and slide our way down a seemingly endless jumble of refrigerator to car sized rocks. By the time we reached the tundra below, a bit bruised but with joints intact, the fog had rolled in and it was nearly dark. We hiked down a bit and then decided to camp, exhausted and cold. We were only three miles downhill to the Noatak River but the fun wasn’t over yet. In the tent, we heard the characteristic quieting of pounding rain turning to snow as we shivered our way through a mostly sleepless night. We rose to a layer of ice and snow, our socks and shoes frozen solid. As we picked our way gingerly down the rocky slope, we wondered if winter had come to stay. Though a bit of snow and cold is not normally a crisis, we are traveling light and are woefully underdressed in wet running shoes and thin jackets.

When we finally reached the stunning Noatak Valley, we felt rung out but relieved and happy – this had turned out to be quite a hurdle. We made our way down the river to our resupply point at 12 Mile Lake, alternately walking in the sun and then boating in the rain. Today the clouds have lifted a little bit and we are hopefully the skies will clear in Bettles so that our plane can arrive. In the meantime, we’re watching a grizzly dig up roots on the other side of the lake and trying not to eat the last of our food.

Turned Back /

The peaks and talus covered passes of the Arrigetch are plastered with snow and yesterday’s 12 hour window of good weather has shut down again. Although we are only 16 miles from the Noatak, Ariel Peak is too snowy to go up and over and we got turned back by wet slabs on Escape Pass. In strong winds and rain we are heading down to brush again, forced to backtrack and try a long and ugly route that we hope will lead to the Noatak. At least rationing food has been easy since we don’t have firewood to cook our meals. Hands down, this is the worst stretch of weather we’ve had since the storms of the Inside Passage. Although our venture into the Arrigetch turned out to be a costly side trip, seeing this spectacular valley has been a treat nonetheless. In a certain way, we’ve come to expect that things often get harder before they get easier – so the easier can’t be too far off!

Aggressive Rain and Bear /

Just when we thought we were on the homestretch, we encountered record rainfall and a stalking bear. Leaving Anaktuvuk Pass, before the rains began in earnest, we found ourselves hiking through mud and tussocks boats on our backs, the water too low for paddling. Ten miles downriver we were able to put in and bounced along the boulders of the John River. The river rose overnight under a deluge and we shivered our way through an otherwise fun day of rapids and swift water. At the confluence with Wolverine Creek we began hiking upstream, searching for the game trails that would ease our passage through the brush and spruce forest. On this road-less and mostly trail-less journey, hoof prints and claw marks are our road signs, leading us to the best terrain and fastest travel. We had heard glowing reports of the smooth walking up Wolverine Creek, but the steady rain led to high water and game trails ended abruptly at the creek’s swollen edges. We crossed the frigid thigh to waist deep water more than thirty times in eight hours before reaching a smaller tributary (for anyone interested in repeating this section, if there’s high water lower your expectations) and the rain continued. We’ve long since adjusted to wet shoes and socks as part of the morning routine but soggy shirts, pants, sleeping bags and tent are harder to embrace. Using our paddle blades and inflation bags we cajoled smoky fires out of wet willows. Along the creek we saw many bears including a grizzly sow with three yearling cubs and the first black bear since the Peel River. From here we worked our way over low misty passes to Nahtuk River. Tired of walking in water, we floated the upper section of this rocky creek before hiking to the dense drainage of the Pingaluk. Here we met our second black bear whose acquaintance we could have done without. Crashing through the last of the willows towards the main river, I heard a rustling in the bushes behind me. I turned to see a pointed nose and cinnamon coat barreling down and had only enough time to raise my arm and shout, the other hand reaching for my pepper spray. The sudden motion gave the bear a moment’s pause and it stopped six feet from me, turned sideways, and took a few steps back. Hearts racing, we pointed our canisters and yelled. With its advance from behind, clearly it had been stalking us but we didn’t know for how long. Unconvinced by its reluctant retreat, we watched as it circled around and began to return, heading slowly and deliberately our way. This time it didn’t stop until Pat sprayed and it ducked away, catching only the edge of the pepper cloud. This encounter turned into a protracted standoff lasting nearly half an hour – the bear advancing, us yelling, throwing poles, moving towards it. Somehow we had to change its perception of who was the aggressor. Eventually, it decided that this meal wasn’t worth the trouble and slowly began to move away. We hated to leave without a definitive end – we didn’t get close enough to spray again and its predatory behavior will likely continue, a threat to other backcountry travelers in the area. We crossed the river as soon as possible, looking warily over our shoulders as we moved through the forest. Among the dozens of bears of we’ve encountered in the backcountry and on this trip alone, this one was an anomaly. Perhaps it hadn’t seen people before, perhaps it thought we were something else. But it looked healthy and fat, not desperate or starving, and its behavior was terrifying. When a human is perceived as prey a large black bear can be a very dangerous adversary.

As we got further downstream and eventually began to paddle we breathed a bit easier. When we finally reached the broad Alatna River, under rainy skies of course, the anxiety had melted away, followed by a deep weariness. But when we arrived at the serenity of Takahula Lake late in the evening, we couldn’t have met a more wonderful surprise. Francesco, whose cabin we used as a resupply point, met us with open arms showing us incredible hospitality and kindness. We have enjoyed a day here to dry out, regroup and find enthusiasm for the next leg through the Arrigetch to the Noatak River. By chance, we happened on two other travelers turned fast friends and we offered a bit of help hauling gear in exchange for the generous use of their boat. Sometimes things have an uncanny way of working themselves out.

Anaktuvuk Pass /

"This is hallowed ground--use of it is a privilege." Theodor Swem's words ring very true for us as we pass through the dramatic landscape of Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve. The most consistent and powerful emotion we have felt as we travel across this vast stretch of largely protected wilderness that flanks the Brooks Range (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Gates of the Arctic & Noatak parks) is that of gratitude. Gratitude for the opportunity to experience a wild place where caribou migrate in the tens of thousands, where tiny Northern Wheatears make their summer home after a long trek from eastern Africa, where we can remember what it means to be humbled. Gratitude for the foresight of key individuals and a conservation movement born largely of reverence and respect. These public lands are a gift to us all and provide the backdrop for the age-old drama of the arctic to continue.

We camped just outside of Anaktuvuk Pass last night and hiked into town this morning under a light drizzle. Steep rocky peaks dressed in fall's yellows and reds jut up all around us. The weather the past few days has been sunny and warm, and our bodies have loved the relatively light loads and firm walking. Abundant blueberries provide a welcome excuse for an occasional sprawl on the tundra--I think we enjoy the soft moss bed as much as the taste of tart berries! For the first time on this journey, we didn't camp alone last night. We met another hiker at the Anaktuvuk River and enjoyed swapping stories before a rainstorm sent us to our tents.

"This is hallowed ground--use of it is a privilege." Theodor Swem's words ring very true for us as we pass through the dramatic landscape of Gates of the Arctic National Park & Preserve. The most consistent and powerful emotion we have felt as we travel across this vast stretch of largely protected wilderness that flanks the Brooks Range (Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Gates of the Arctic & Noatak parks) is that of gratitude. Gratitude for the opportunity to experience a wild place where caribou migrate in the tens of thousands, where tiny Northern Wheatears make their summer home after a long trek from eastern Africa, where we can remember what it means to be humbled. Gratitude for the foresight of key individuals and a conservation movement born largely of reverence and respect. These public lands are a gift to us all and provide the backdrop for the age-old drama of the arctic to continue.

We camped just outside of Anaktuvuk Pass last night and hiked into town this morning under a light drizzle. Steep rocky peaks dressed in fall's yellows and reds jut up all around us. The weather the past few days has been sunny and warm, and our bodies have loved the relatively light loads and firm walking. Abundant blueberries provide a welcome excuse for an occasional sprawl on the tundra--I think we enjoy the soft moss bed as much as the taste of tart berries! For the first time on this journey, we didn't camp alone last night. We met another hiker at the Anaktuvuk River and enjoyed swapping stories before a rainstorm sent us to our tents.

We picked up our packrafts and food resupply from the post office (thanks Ash!) and are getting geared up to head out on the John River tomorrow morning. This is our last planned town stop before Kotzebue so we're enjoying a few amenities before leaving. What we will miss most in the next few weeks is not a shower or a proper meal (though they are awfully nice!), but the pleasant surprises of town visits. In every community we've visited, we've found kindness and generosity, often in unexpected places. We've learned so much from people with different lifestyles but shared human values. And hearing from all of you via the blog (a new experience for us), email, phone, and thoughtful notes in our resupply boxes is such a treat. It's not that we feel lonely when we're out but simply that the input from others has helped to shape our journey in a very positive way. For me, this has been the biggest surprise of the past 5 months. I didn't expect that venturing out into the wilderness would provide such a strong sense of human connection--but many of the best things in life are impossible to predict.

Sag River /

The snowstorm of August 7th lingered on the peaks and ridges, making for difficult travel over loose scree as we climbed over a 6500’ pass. This turned out to be a fitting day for our anniversary as we crested an impressive viewpoint and picked our way down to the glacier below. Light footed on the ice and rock, we hadn’t expected to encounter winter again so soon. That night, camped alongside the Sag River we woke to a curious shrike and a chorus of howls. Five wolves bedded down on a bench above us, watchful as we ate breakfast around the morning fire. Traveling over passes and along their drainages, we’ve found good and varied walking. With light packs we can move quickly and are feeling strong, the mountains whipping us quickly into shape. Yesterday afternoon we hit the dust of the haul road – it’s strange to see rumbling trucks after so many miles of wilderness. Ducking under the pipeline we felt out for our resupply barrel, left out by friends on their way to go caribou hiking. We gorged ourselves on the treats within (thanks Dan, Mom and Dad, Eleanor and Rich) and are ready for the next push to Anaktuvuk Pass.

Chandalar River /

Looking across the Chandalar River, we wondered if mailing our packrafts to Anaktuvuk Pass had been the best choice. A morning swim suddenly didn’t seem so appealing. Eventually I waded in and began to work my way across, using a contorted breast stroke that allowed me to push my pack with my chin. Pat employed a different technique that involved a lot of splashing; he claims it was a hybrid between a side stroke and a one-armed crawl. With the cold water and our awkward loads, the swim felt a lot longer than the equivalent three to four laps in a pool. Once across we spotted several grey headed chickadees, an Arctic species about which little is known. The next day, a grizzly caught our scent and lumbered away across the red-gold valley. Hunkered down behind a spine of rock, we rose to meet the gaze of two grey wolves working up the ridge below us. When possible we opt for the high routes, trading tussocks for sidehilling, burning calves, and solid ground. For anyone who hasn’t had the joy of experiencing tussocks firsthand, they deserve a mention. Tussocks are mounds formed by cotton grass and are a common feature of arctic tundra. Hiking through this deceptively attractive groundcover is like balancing on lopsided medicine balls interspersed with stepping in pools of muddy water. The “controlled stumble” is a very fitting description of this motion. We spent last night camped in a valley with 200 caribou grazing nearby. Today it is snowing. Each day is full of surprises.

Arctic Village /

Yesterday turned out to be one of those days. Swatting bugs and shivering, we wondered if perhaps we'd taken the wrong channel and returned mistakenly to the Mackenzie Delta. Our grumpiness stemmed from heavy, cold rain and flashbacks of endless packrafting through muddy sloughs. The landscape of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has changed dramatically over the past 10 days, and after delighting in the alpine tundra of the high country we've stumbled back into black spruce wetlands.

Leaving the arctic coast from Kaktovik felt a bit like saying goodbye to a friend, with no plans to see each other again soon. The transition from ocean to tussocks seemed sudden and rushed. Before I'd had time to contemplate departing this magical interface between sea & sky, the last mirages of light on ice had disappeared from view. A lonesome caribou calf, thin and harried by warble flies, approached us curiously and echoed my melancholy sentiments. Though it seems hard to imagine in our fast-paced modern world, sometimes even walking feels too fast. But with the end of summer quickly approaching, there's only so much time to wax philosophically. Yesterday's chill reminded us that we'd best keep moving. It won't be long before rain turns to snow up here and there are still many mountain passes to cross.

Yesterday turned out to be one of those days. Swatting bugs and shivering, we wondered if perhaps we'd taken the wrong channel and returned mistakenly to the Mackenzie Delta. Our grumpiness stemmed from heavy, cold rain and flashbacks of endless packrafting through muddy sloughs. The landscape of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge has changed dramatically over the past 10 days, and after delighting in the alpine tundra of the high country we've stumbled back into black spruce wetlands.

Leaving the arctic coast from Kaktovik felt a bit like saying goodbye to a friend, with no plans to see each other again soon. The transition from ocean to tussocks seemed sudden and rushed. Before I'd had time to contemplate departing this magical interface between sea & sky, the last mirages of light on ice had disappeared from view. A lonesome caribou calf, thin and harried by warble flies, approached us curiously and echoed my melancholy sentiments. Though it seems hard to imagine in our fast-paced modern world, sometimes even walking feels too fast. But with the end of summer quickly approaching, there's only so much time to wax philosophically. Yesterday's chill reminded us that we'd best keep moving. It won't be long before rain turns to snow up here and there are still many mountain passes to cross.

We shed our angst about leaving the coast as we began to climb toward the peaks of the Brooks Range, growing larger with each step. The enticing whitewater of the Hulahula beckoned below, but our path carried us south, back toward drainages of the Yukon River. Shifting assemblages of birds and wildlife mirrored the changes we saw in the landscape. We left jaegers and plovers behind as we climbed up toward Gilbeau Pass. Dall sheep traversed steep scree above us as tattlers and wheatears greeted us at the crest of the divide. Dropping back down the other side, we followed caribou trails over seemingly unlikely routes that proved to offer the smoothest travel. We've learned to trust this animal intuition, moving forward with a bit of faith rather than balking at deeply rutted paths up hillsides and across rivers. It's hard to imagine that several thousand caribou have got it wrong for all these years.

The perfect alpine tundra ended far too soon as we hiked down to the Chandalar River. Nearly 50 miles north of Arctic Village, we saw trees again. In this beautiful, broad valley, signs of moose reappeared and Spotted Sandpipers flitted along the riverbank. Where we began paddling, the river was fast and fun and we covered miles through the braided channels quickly in the warm sunshine. That night, a full moon rose over the gravel bar as we relaxed by the fire. Perfect. A day and a half later we weren't loving it quite so much. Several large flocks of Rusty Blackbirds and a caribou swimming the river provided welcome distractions from the slow meanders as the rain dripped down our necks. Our raingear has seen better days, especially evident when sitting in a puddle of water for hours on end. But it can't be pleasant ALL the time or it would hardly be an adventure. We were lucky to find the tribal council office still open in Arctic Village and we've since dried out at the school, ready for the next leg to the Haul Road. This is the first road we will cross since the dirt of the Dempster Highway more than a month and a half ago. Lovely wild places for us all to roam.

Signs of Fall /

As we left the ocean and headed inland, the coastal plain felt deserted but for a few orphan caribou calves and the shrieks of jaegers defending their young. Now, hiking up the Hulahula River, we are nearing the continental divide, following the tracks of thousands of caribou. It seems strange to be traveling south after so many months of northward progress and already we notice the first signs of fall, blueberries are ripening and the sun dips behind the mountains each evening, the closest thing we’ve seen to a sunset in weeks. Yesterday, we watched a wolverine watch us, got stung by ground nesting bees, and listened to the liquid calls of upland sandpipers. We feel humbled by the scale of this giant glacial valley, where boulders and bears have a way of disappearing into the hillsides and broad peaks stretch beyond view.

Kaktovik /

Check out the new photo gallery here.

We have arrived at our most northerly latitude, 10 miles north of the 70th parallel. Nearing Kaktovik, our footprints were dwarfed by polar bear tracks and the landscape felt fantastically wild. Walking more than two hundred miles along a coastline with little information besides outdated maps proved to be well worth the slog through the delta. We were thrilled to be seeing this landscape on foot, though we had initially considered rowing or paddling this stretch. We wanted the intimacy of wandering along the beaches and the freedom of not being tethered to a big boat, not to mention avoiding the logistics and expense of dealing with getting it shipped back home.

We have arrived at our most northerly latitude, 10 miles north of the 70th parallel. Nearing Kaktovik, our footprints were dwarfed by polar bear tracks and the landscape felt fantastically wild. Walking more than two hundred miles along a coastline with little information besides outdated maps proved to be well worth the slog through the delta. We were thrilled to be seeing this landscape on foot, though we had initially considered rowing or paddling this stretch. We wanted the intimacy of wandering along the beaches and the freedom of not being tethered to a big boat, not to mention avoiding the logistics and expense of dealing with getting it shipped back home.

After crossing the Alaskan border, long ribbons of gravel and sand stretched as far as the eye could see. Many times these "reefs" or barrier islands are only a few feet above sea level and dramatically narrow. At times they pull several miles offshore and we were fortunate never to be caught in a storm. Though surrounded by icebergs and large river deltas, fresh water posed one of our biggest challenges. On one such day, we hiked with 20 lbs of water on our back for several hours before discovering it was brackish. Typically we would paddle to the mainland shore in search of water, but were often disappointed to find many of the sloughs and small ponds contaminated by the sea even far from the shore's edge. Although the tides fluctuate by only a foot (compared to 20+ feet in the Inside Passage), the tundra is incredibly flat where river deltas meet the ocean. Even a small change in water levels, like that brought about by wind (or the threat of sea level rise due to climate warming) can flood a large area. Coastal erosion along the sea bluffs is occurring rapidly, up to 30' a year according to permafrost scientists we met at Herschel Island. To avoid these messy banks, we often walked the tundra, which became better as we traveled west. In one tight spot, we found a rough-legged hawk nestling at the base of a bluff that had recently slid, its dead sibling nearby.

Caroline has been pointing out new bird species as quickly as I can forget the previous ones. The coastal plain is full of life--cranes, jaegers, longspurs, eiders, plovers, 4 species of loons, caribou, musk ox, and grizzlies. We've seen ringed and bearded seals and few belugas but we're too early for bowheads this far west with pack ice still near shore.

From here we head almost due south into the white-capped peaks of the Brooks Range that stand in sharp contrast to the coastal plain. Our final goal is to reach Kotzebue on the Bering Sea, more than 1,000 miles away, before freeze-up. The approach of winter in the north has set the timeline for this trip and so far we are only a few days behind our estimates. We've been lucky to have met many knowledgeable and generous people along the way who have fed us, housed us, and educated us about the Arctic. We look forward to traveling in the mountains again, though this will undoubtedly bring a new set of challenges.

Icy Reef /

We crossed the border into Alaska yesterday morning, passing from Ivvavik National Park to the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Since we left Herschel Island, we've seen belugas, seals, and much colder and wetter weather. Walking along a spit littered with whale bones and eider nests, dense fog obscured all but the waves lapping at the shore. Waking from this grey haze to sunshine the next morning, we looked out on a sea of icebergs stretching to the far horizon. Caribou and their calves grazed along the lush coastal plain, wedged between the mountains and the ocean. Moving through this land of extremes we are wide-eyed at its vastness. We've alternated between hiking on the beaches and tundra and for one stretch cruised along huge sheets of ice still held fast to shore. We are now traveling on Icy Reef, a thin shelf of sand and gravel that parallels the mainland.

Herschel Island /

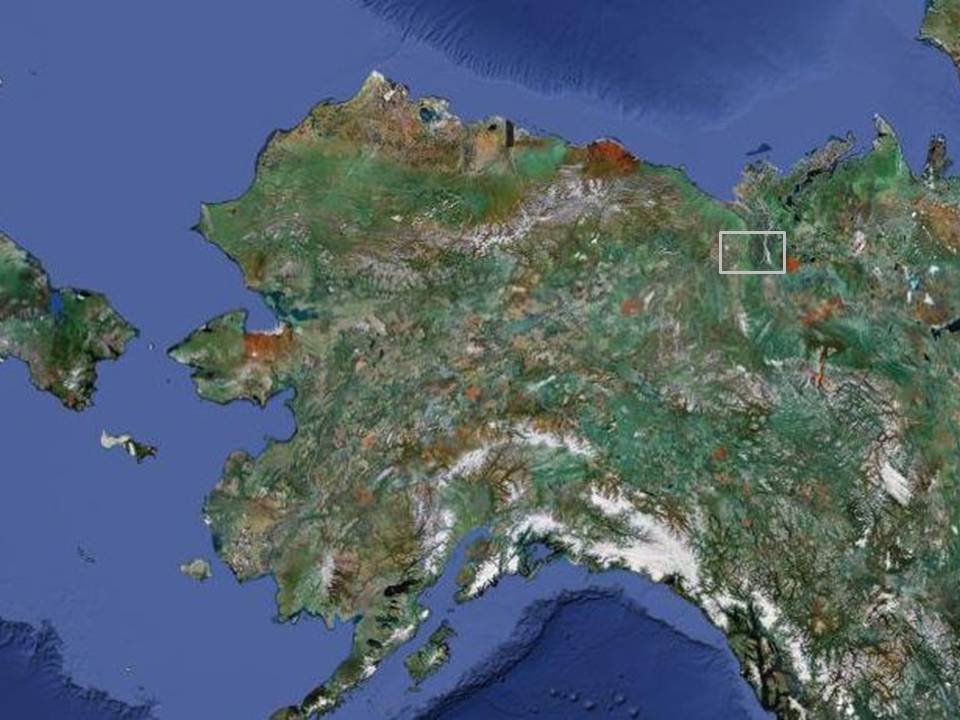

After dragging our boats through ankle deep water more than a half mile offshore, we finally said goodbye to the Mackenzie delta. By the time we reached deeper water, northeasterly winds had picked up. This introduction to the Arctic Ocean was a wet one for Pat as he capsized in large following seas compounded by the outflow of the Blow River. I looked back to see in slow motion his boat crest sideways and then topple. He was able to right and then climb back in still holding his paddle and we continued toward the bluff onshore for an exciting surf landing. As the seas grew larger, we were happy to pack up the raft and walk the beach. We passed a whaling camp near Shingle Point and were treated to a hot meal of caribou soup. The Inuvialuit people of this region have showed us incredible hospitality, sharing their knowledge about the land and our route. Travel along the coast has re-energized us – the beaches offer good walking and the tundra is peppered with wildlife. We’ve seen caribou in velvet, musk ox grazing on a spit, and many nesting peregrine and gyrfalcon. Eiders, scoters and long tailed ducks are congregating to raise ducklings or molt. Yesterday we wove our way through towering icebergs to Herschel Island to pick up a re-supply and enjoy this amazing place. Next we’ll head northwest to Kaktovik, 165 miles down the coastline. [googlemaps https://maps.google.com/maps?f=q&source=s_q&hl=en&geocode=&q=Herschel+Island,+Yukon,+Unorganized,+YT,+Canada&aq=0&oq=herschel+island+&sll=37.0625,-95.677068&sspn=38.41771,86.572266&t=h&ie=UTF8&hq=&hnear=Herschel+Island&ll=69.579457,-139.076206&spn=2.125941,10.821533&z=7&output=embed&w=425&h=350]

Photo Gallery Update /

Caroline and Pat mailed some new photos from Ft McPherson that arrived today. Check them out here.

Lightning, Rainbow, Moon and Sun /

We made it to the Arctic Coast after the delta released us from its vicious hold. It’s much nicer here, tons of birds and expansive views. Pulled two all-nighters, saw a grizzly on a marine mammal carcass and were pursued by moose in the shallow waters of the Arctic Ocean. Saw lightning, rainbow, moon and sun all on one horizon. It feels like we’re in a dream world. We are now walking and puddle jumping across the remainder of the delta, the beaches several miles ahead. In the map below, Caroline and Pat are approximately 6 miles from the Arctic Ocean on the western edge of the delta.

[googlemaps https://maps.google.com/?ie=UTF8&ll=68.972193,-135.681152&spn=1.072348,4.916382&t=h&z=8&output=embed&w=425&h=350]

Mackenzie Delta /

We have clawed, pried and cursed our way through the first 90 miles of the McKenzie delta, trying to find some humor in the ridiculousness. On our first night out we measured all the squiggles of the meandering channel on the map and realized we had over 200 miles of boating to get to the arctic coast, not the 140 we had originally estimated. The delta is a great place for ducks, swans, loons and terns but has been less hospitable to us. With a strong north breeze overpowering the weak current it would be faster to travel up river. We are tired not just from short and restless night, and physical exertion, but deep down tired. Tired of the bugs, the mud, the brushy cut banks and most of all, the endless headwind that wears on our nerves and our joints. The coast will be a much needed break from the monotony of flat water pack-rafting and we are exciting to start walking again. Fortunately as time passes usually so do the miles. In the meantime we hope for calmer weather. *No new photos but Caroline was able to send their approximate location so we can picture where they are based on some Google Map screen shots. If you want to explore a map on your own they are approximately 10 miles south of Aklavik, NT, Canada on a western channel of the river.

Solstice /

It’s not often we remember exactly where we were 10 years ago to the day. On this year’s summer solstice, however, the recall was easy. As we drifted toward the confluence of the Wind and Little Wind rivers, we met a familiar view of the low-lying Illtyd Mountains. On our first trip into the Wind River drainage in 2002, we hadn’t heard of a packraft but, similar to this visit, intended to hike in and paddle out. The concept was beautiful—we would go “ultra-light,” bringing only the tools necessary to build the canoe rather than the canoe itself. These tools included a bow saw blade, small axe, froe, drawknife blades, and pot for steaming roots. We spent 2 months hauling food and gear over the continental divide, building a bark canoe at the headwaters of the river (spruce as no birch were available), and, eventually, paddling the 300 miles to Fort McPherson. The enormous amount of food we carried in, though insufficient to meet our needs, made travel slow and cumbersome, forcing us to double carry. The bright idea, though ultimately executed, had us hanging by the skin of our teeth—short on food, short on time, and with little safety margin.

It’s not often we remember exactly where we were 10 years ago to the day. On this year’s summer solstice, however, the recall was easy. As we drifted toward the confluence of the Wind and Little Wind rivers, we met a familiar view of the low-lying Illtyd Mountains. On our first trip into the Wind River drainage in 2002, we hadn’t heard of a packraft but, similar to this visit, intended to hike in and paddle out. The concept was beautiful—we would go “ultra-light,” bringing only the tools necessary to build the canoe rather than the canoe itself. These tools included a bow saw blade, small axe, froe, drawknife blades, and pot for steaming roots. We spent 2 months hauling food and gear over the continental divide, building a bark canoe at the headwaters of the river (spruce as no birch were available), and, eventually, paddling the 300 miles to Fort McPherson. The enormous amount of food we carried in, though insufficient to meet our needs, made travel slow and cumbersome, forcing us to double carry. The bright idea, though ultimately executed, had us hanging by the skin of our teeth—short on food, short on time, and with little safety margin.

This time around, we employed a different strategy, moving fast and light, covering the same number of miles in 13 days rather than 60. The packrafts and their amazing portability—weighing in at under 8 lbs fully outfitted—made this feasible. Our route was different as well, hopscotching between floating and hiking, connecting adjacent river valleys.

From the Tombstone Mountains, we hiked into the West Hart River, passing alpine flowers in bloom, a lanky brown-black wolf, and several caribou. Nests housing the tiny eggs and downy chicks of Arctic Warblers, White-crowned Sparrows, and other breeding songbirds dotted the thickets of willows and alders. After 25 miles of walking we finally had enough water to begin bumping along and we happily left the mud and tussocks behind. Knowing almost nothing about the headwaters of the river, we were anxious to jump in but uncertain about what it might bring. The river became more exciting as we traveled downstream, encountering plenty of whitewater to keep us on our toes. Class III ledges and boulders followed mellow gravel bars, winding from colorful canyon walls to forested bluffs. A moose and her brand new calf swam the river just ahead of us. Mergansers and Harlequin Ducks bobbed along in the waves. Too soon we reached the confluence with the main Hart River where we loaded the boats onto our backs once again.

We waded across Waugh Creek’s crystal clear water many times, following game trails through willows and alder. The creek led us by deep pools beneath rock faces that later gave way to wide valleys with massive ice as thick as 6 ft deep, 1 mile long, and half a mile wide. Called “aufice,” or “glacier” by locals, it is formed by freezing from the “bottom up,” in which layer after layer of water (overflow) builds throughout the winter. Unlike the deep snow in the Tombstones, the ice provided good walking with a break from the bugs. Tussocks with swarms of mosquitoes and blazing sun slowed our progress, sending us search in vain for better terrain. Finally, on Forrest Creek, we gladly traded bushwhacking for cottongrass, then at last said enough and dropped our packs and inflated our rafts. We put in early and got hung up early, unable to outrun mosquitoes as we drifted along. The Little Wind brought plenty of water for our boats and at last we spilled into the Wind River, familiar ground to us. As the walls of the Peel Canyon rose around us, an an eerie “chreee” of a Red-tailed Hawk (in our minds-eye, perhaps the same bird we heard 10 years earlier) set the tone as we slid into a wave train. This time, with lower water levels and manufactured boats, we were relaxed. Last time, we found ourselves way out there, gripping whittled paddles, unsure of the breaking point of our canoe. Thinking back to summer solstice spent at our canoe-building camp on the upper Wind River—a couple of kids with an outrageous idea and a heap of optimism—our practicality on this go-around might almost be called boring. But, fortunately, things rarely go according to plan.

70 miles from Ft McPherson, as we choked on mosquitoes and smoke from forest fires burning all around us, we also remembered why we pulled 16 hour days in the canoe, paddling mile after mile along the sluggish river. But this time, speed was not on our side. Though the packrafts have made this trip possible, they can’t compete with the bark canoe in flatwater paddling. With a stiff headwind leaving us at a near standstill, one and then both of us retreated to the shoreline, stumbling downriver through mud and brush. Sinking up to our knees in the shoe-eating muck, at times we had to resort to a full crawl to extricate ourselves. Thunder and lightning storms raged, stirring up dust devils on the gravel bars and casting a dramatic hue to our misadventures. Morale waned a bit as what should have been an easy day of boating turned to two days of mud-bogging on empty bellies. Persistent aches and pains have been nagging as well—it’s often a blurry line between chronic discomfort (which is a given on a trip like this) and injury. This leg seemed to bring some of the highest highs and lowest lows yet, and the mud and mosquitoes incited the latter. There is a beauty in the rawness of a place like this, in which crossbills and goshawks thrive but humans suffer. But appreciating the scenery through a headnet takes a certain kind of grace and humility of which I find I’m only intermittently capable.

A box of cookies and quart of chocolate milk helped to lift our spirits as we made it to the joint store/post office/gas station in Ft McPherson. Since arriving here, we’ve already met several folks whose families have hunted, fished, and trapped in this area for generations, sharing stories about travel by dog team, canoe, and Skidoo. They also cautioned us about the vulnerability of the entire Peel River watershed to development pressures and ask that we help to bring awareness to these issues (ProtectPeel.ca).

As we head north toward the Arctic coast, we will leave the trees behind and enter the enormous web of the McKenzie River Delta. We have another 140 miles of boating (let’s hope that north wind goes easy on us!) and 90 miles of walking to reach Herschel Island. Internet and phone are hard to come by, so updates and photos may be a bit delayed but we’ll do our best to keep them coming. We’re thinking of you all, especially Kate & Nate and their new arrival! Thanks as always for the encouragement and emails—they mean a lot to us!

Little Wind River /

A quick update from Caroline and Pat via satellite phone. Caroline and Pat reached the 2,000 mile mark of their journey on the solstice. They made it to the head waters of the Little Wind River and are travelling onto the Wind River, which they hope to make in two or three days. They can raft for the most part but some of the stream is braided and shallow. They are having very warm and sunny weather which also makes for lots of mosquitoes and a very warm tent.

Several people have inquired as to whether they would be passing by the site of their spruce bark canoe building adventure on the Wind River about 10 years ago. They will actually enter the Wind River about 70 miles downstream of the site.

Tombstone Mountains /

Traveling seventy miles through the Tombstone Mountains from Dawson, we cursed ourselves for not fully appreciating the canoe! Dense alders and willows, postholing in thigh-deep snow, and mosquitoes were the tolls required to get a glimpse of the stunning granite spires for which these mountains are known. Locals in Dawson pointed us toward a route that followed part of the historic, 100-year-old "ditch" that diverted water to the goldfields at Bonanza Creek. This ambitious engineering feat has been compared in scale to the Panama Canal and some of the same steam-powered backhoes were used in the construction of both projects. With recent warm conditions and accelerated snowmelt, creeks were swollen and much of our route was very wet and muddy. In the low country, we encountered dense brush and muskeg and in the high country, met deep snow, leaving little in between for decent travel. Occasionally we found good caribou and other game trails, but even these had largely turned to gushing streams in the wet conditions. The route we eventually chose, a compromise between negotiating steep terrain and high water levels, led us over two passes and across several icy creeks, one more than waist-deep. We found ourselves punching through soft, deep snow for hour after hour in running shoes, following the tracks of caribou and bears, who travel these passes regularly. Several alpine lakes in the area provide nesting habitat for sea ducks, but these were still ice-covered as we passed. A single White-winged Scoter surfing the whitewater of Little Twelve Mile River may have been biding her time waiting for the late break-up. American Pipits, Snow Buntings, and Gray-crowned Rosy-finches braved the snow to find small patches of exposed tundra and a pair of Golden Eagles greeted us, along with wind and snow showers, at 6000'. Unfortunately, rowing, packrafting, and canoeing left us with tough hands but tender feet and it will take some time to harden up our soles again.

We left the dramatic peaks and expansive views of the Tombstones and hiked down to the Park's interpretive center, where staff generously held our resupply, left by my parents on their recent visit. We won't have a rest day here as we're already cutting into provisions for the next leg and need to keep moving. We're sending this update on a borrowed internet connection as there is no phone and only limited infrastructure here. As we travel through increasingly small and remote communities, communication will be much more limited.

We're heading off today on what we anticipate may be one of the most challenging legs of the trip. Our plan is to hike into the Hart River, packraft a section of this, then cross through the Wernecke Mountains to the Little Wind River. From here we hope to paddle to the "big" Wind River and rejoin our route to Fort McPherson, which we did in a bark canoe almost exactly 10 years ago. We have little information about the headwaters of these rivers and hope they will be suitable for packrafting. If not, the hiking will be slow and painful. Even as proposed, we have a long slog through tough terrain ahead of us. We will keep our eyes out for trails and route clues left by caribou, moose, wolves, bears, and other critters who travel through these wild lands.