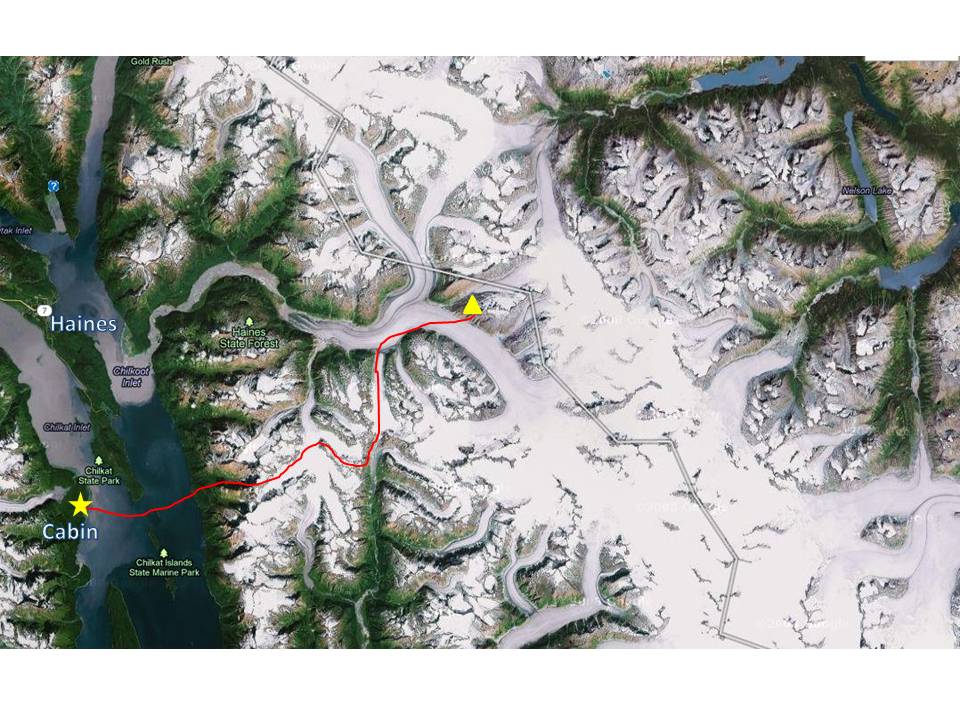

Check out the new gallery of Haines to Whitehorse photos. We arrived in Whitehorse yesterday after our trek up and over the mountains and into the headwaters of the Yukon River. Shortly after launching from the cabin in our packrafts, we found ourselves treading water into a stiff north breeze. Though we were able to ferry sideways, we made almost no headway, continuing to slip to the south. These small inflatable boats are easily pushed around, especially when loaded with packs and skis, and a headwind can be a showstopper. As whitecaps began lapping at our dangling skis, we considered abandoning the crossing. Fortunately, the wind eased rather suddenly and we were able to continue on to Seduction Point and across to the east shore. Along the way we encountered a group of incredibly curious and playful sea lions. We felt a bit vulnerable in our beach ball-like rafts as we watched them swim in the clear water beneath our boats, flipping and diving just feet from us. We finally landed on the rocks north of Yeldalga Creek and loaded the boats onto our packs for the long uphill slog.

Travel through the mature hemlock forest was steep but surprisingly decent for southeast Alaska. Thankfully, with spring's late arrival, the Devil's Club had not yet sprung up. We hit snow line at approximately 1500' and were thrilled to take the skis and climbing skins off our backs and put them on our feet. By late evening we made it up to treeline at the base of the cirque. We got up early the next morning, hoping that the snow would firm up overnight, but with warm temperatures that didn't drop below freezing, the snow remained wet and heavy. According to a local pilot, the last spring storm cycle dumped 6' in the mountains--this made for good coverage but slow trailbreaking as we headed up to the col. As we scrambled quickly over avalanche chutes, we felt confident that the previous days' warm temperatures and sunshine had cleared most of the snow from the rock faces above. Light rain turned to snow as we neared the col at 5000'. Descending eastward over the other side didn't offer the great ski run we had hoped for, but instead left us slowly picking our way down in flat light and fog. Several wet slides came down from the adjacent saturated slopes. Relieved to reach the valley below, we followed the broad Sinclair Glacier (otherwise known as the "Dead Glacier") downslope . Due to the wet, rotten snow conditions, we decided to try an alternate route to access the Mead Glacier (slightly different from the hypothetical map posted last week). This option would keep us off the steeper slopes prone to slides but presented the challenge of getting off of one glacier and back onto another.

We continued down several thousand feet to the glacier's terminus. Crevasses were easily avoided so we skied unroped and were glad to find an easy exit onto the patchy snowfields of the creek bottom. Mountain goats traveling on precarious faces above us kicked down an occasional rock. Alternating between skiing and carrying our skis through talus fields and along the brush and gravel that lined the river, we continued downstream. We made camp on a knoll overlooking a glacial lake with ice fins towering above. A few hardy ducks, gulls, and terns frequented the lake and we watched a beautiful black bear amble by. In the morning we worked our way across several creeks to the east shore of the lake but quickly realized that access onto the glacier would not be possible here without technical climbing gear, which we lacked. From our new perspective, the western shore of the lake looked more promising. All of the water from the creeks and lake funneled below the glacier, producing a bridge of rock-covered ice. We traversed around the lake and before long we were walking on the broad, flat Mead Glacier. A moon-like landscape of rock-studded blue ice soon gave way to snow and we happily donned our skis again. Trudging along in a drizzle, we veered north off the Mead and camped on the medial moraine of an unnamed glacier just before the Canadian border.

A headwind greeted us in the morning as we continued toward the divide. In glaringly flat light, we were surprised to see other travelers in this starkly white landscape. What looked like a rock from a distance turned out to be a Trumpeter Swan enjoying a bath in a perfectly blue glacial lake. We watched a small flock of swallows fighting their way into the fierce headwind, toggling back and forth to switchback into the gusts. Yellowlegs and pipits called as they flew by in the distance and a Rough-legged Hawk passed overhead before catching a thermal and rising into the clouds. This mountain pass appears to be a prominent flight path for birds heading from the Katzehin River into the interior. At approximately 4000' the steady climb eased and our skis tipped downhill into the Yukon River watershed. Though tidewater of the Pacific lies only 25 miles away, snowmelt here will travel nearly 2000 miles to the Bering Sea. Happily, our descent off the glacier posed no steep icefalls to negotiate, in contrast to what is typical on the west side of the range. After passing several glacial lakes, we reached a creek that would become the Swanson River. The dry pine forest immediately presented a dramatic contrast to the hemlock and spruce of southeast Alaska. We left the river as it dropped into a rocky canyon, only to find that we were boxed in by a similar canyon formed by a tributary creek on the other side. We skied upcreek until we found a snowbridge to cross--this turned out to be lucky timing as the bridge collapsed overnight while were camped on the far side.

The next day we skied through the forest and along gravel bars. Before long, tree wells became more abundant than the snow and we wasted time and energy wiggling through tight spots, sliding into holes, and extricating ourselves from various awkward positions. Eventually we reached a cutbank with a waterfall and cliffs above, leaving the river as the only option for travel. We inflated the boats and, with skis and heavy packs lashed onto the bows, slid into the swift current. We scouted the first several sections, occasionally carrying around shallow rocks. Soon our confidence increased and we rounded bend after bend, loving the free ride down this river we had not anticipated being able to float. Several miles later, the turquoise waters of Tagish Lake appeared. This formed the gateway to the inland waterway we would follow for the next 120 miles.

The lake offered fantastic camping and gorgeous views. After spending seven weeks on the ocean, we had to retrain ourselves to stop thinking about tides and currents and remember that we could simply dip our cup in for a drink. No sea lions or whales would be coming by for a visit--distractions we soon missed. A steady tailwind helped our progress without stirring up the large waves encountered on the ocean. When we tired of flatwater paddling, we walked the shoreline. In clunky ski boots this made for slow going but we enjoyed seeing the abundance of wolf, bear and other tracks and hearing the lively chorus of songbirds in the forest. We watched caribou, moose, fox, porcupine, and beaver travel along the beaches and shorebirds feed in the shallows. Passing by the Tagish Wilderness Lodge, owners Sarah and Gebhard treated us to a delicious hot meal and helped stretch our provisions for the last 65 miles to Whitehorse. We enjoyed hearing stories about their remote year-round existence and the operation of an off-the-grid lodge. We also learned that the ice had departed from the lake only a few days prior to our arrival.

Marsh Lake, true to its name, offered muddier walking but lots of bird activity. We saw large flocks of shovelers, pintail, wigeon, teal, swans and many of the same species that accompanied us along the coast--White-winged Scoters, mergansers, goldeneye, Long-tailed Ducks, Whimbrel (perhaps some of the satellite-tagged birds whose route we have been paralleling!), yellowlegs, and Pacific and Red-throated loons. Spotted Sandpipers and Semi-palmated Plovers busily worked the shorelines. Warblers, sparrows, thrushes, grouse, snipe and a Boreal Owl called and sang late into the evening.

Finally we felt the welcome pull of the Yukon River. We drifted under the bridge of the Alaska Highway, 20 river miles from Whitehorse. Still slow-moving at this point, we paddled along the river for most of the day before reaching the dam that provides hydropower for the area. We pulled out and walked the final stretch to the campground. The post office was closed by the time we made it to town, so we tromped around the grocery store in ski boots, anxious to swap these out for lightweight hiking shoes. As often happens in the north, we randomly crossed paths with friends on other adventures during our short stay in Whitehorse. The next leg will be a vacation of sorts as we travel by canoe down the Yukon River to Dawson. The canoe will be speedy compared to the packrafts and space is much less limited--this means more food and a book to read! Thanks for your comments and emails--we enjoy hearing from everyone along the way.